Abolitionists and Anti-Slavery Activists

The following is a list of American abolitionists, anti-slavery activists and opponents of slavery. This list was drawn from a number of primary and secondary sources. At present, this list includes more than 2,500 names. In this list are African American and Caucasian abolitionists and anti-slavery activists.

We are including in this list all anti-slavery activists and opponents of slavery, whatever their motives, whether humanitarian, or economic and political. Some of these individuals were against slavery in principle, on moral grounds, while they possessed and exploited slaves themselves. We are also including individuals regardless of their orientation toward the ending of slavery. Among the abolitionists, we are including those whose methods were radical, immediatist, moderate and gradualist.

We use the term "abolitionist," but we intend to include all opponents of slavery.

This list is a work in progress. We intend to continue our research and add more names to this list. We will also be including biographical sketches of each of these individuals and additional references. |

|

|

|

Return to Top of Page

|

|

AARON, b. 1811, African American, former Virginia slave, anti-slavery orator. Wrote Light and Truth of Slavery: Aaron’s History, 1845. (Gates, Henry Louis, Jr., & Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, eds. African American National Biography. Oxford University Press, 2013, Vol. 1, p. 1.)

|

|

AARON, Samuel, 1800-1865, Morristown, NJ, educator, clergyman, temperance activist, abolitionist. Manager, American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS), 1840-1842. Vice President, 1839-1840, Executive Committee, American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. (Appletons’ Cyclopaedia of American Biography, 1888, Vol. I, p. 1. Dictionary of American Biography, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1936)

AARON, Samuel, educator, b. in New Britain, Bucks co., Pa., in 1800; d. in Mount Holly, N. J., 11 April, 1865. He was left an orphan at six years of age, and became the ward of an uncle, upon whose farm he worked for several years, attending school only in winter. A small legacy inherited from his father enabled him at the age of sixteen to enter the Doylestown, Pa., academy, where he fitted himself to become a teacher, and at the age of twenty was engaged as an assistant instructor in the classical and mathematical school in Burlington, N. J. Here he studied and taught, and soon opened an independent day school at Bridge Point, but was presently invited to become principal of Doylestown academy. In 1829 he was ordained, and became pastor of a Baptist church in New Britain. In 1833 he took charge of the Burlington high school, serving at the same time as pastor of the Baptist church in that city. Accepting in 1841 an invitation from a church in Norristown, Pa., he remained there three years, when he opened the Treemount seminary near Norristown, which under his management soon became prosperous, and won a high reputation for the thoroughness of its training and discipline. The financial disasters of 1857 found Mr. Aaron with his name pledged as security for a friend, and he was obliged to sacrifice all his property to the creditors. He was soon offered the head-mastership of Mt. Holly, N. J., institute, a large, well-established school for boys, where, in company with his son as joint principal, he spent the remainder of his life. During these years he was pastor of a church in Mt. Holly. He prepared a valuable series of text-books introducing certain improvements in methods of instruction, which added greatly to his reputation as an educator. His only publication in book form, aside from his text-books, was entitled “Faithful Translation” (Philadelphia, 1842). He was among the early advocates of temperance, and was an earnest supporter of the anti-slavery cause from its beginning. Appleton’s Cyclopaedia of American Biography, 1888, Vol. I. pp. 1.

|

|

ABBEY, Cheney, New York, American Abolition Society (Radical Abolitionist, Vol. 1, No. 1, New York, August 1855)

|

|

ABBOTT, Gorham D., Boston, Massachusetts. Member of the American Colonization Society, Boston Auxiliary. Active in leadership of Society. Published The Colonizationist and Journal of Freedom, a monthly magazine. (Staudenraus, P. J. The African Colonization Movement, 1816-1865. New York: Columbia University Press, 1961, pp. 201, 204)

|

|

ACKLEY, John, abolitionist, officer of the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery (PAS), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Nash, 1991, p. 131)

|

|

Adair, William A., Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, abolitionist, American Anti-Slavery Society, Manager, 1837-40

|

|

ADAM, William, Cambridge, Massachusetts, abolitionist, American Anti-Slavery Society, Manager, 1843-45

|

|

ADAMS, Arianna, African American, member, Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society (BFASS). (Yellin, 1994, p. 58n40)

|

|

ADAMS, Charles Francis, 1807-1886, Vice President, Anti-Slavery Free Soil Party, newspaper publisher and editor. Son of former President John Quincy Adams. Grandson of President John Adams. Opposed annexation of Texas, on opposition to expansion of slavery in new territories. Formed “Texas Group” within Massachusetts Whig Party. Formed and edited newspaper, Boston Whig, in 1846. (Adams, 1900; Duberman, 1961; Goodell, 1852, p. 478; Mitchell, 2007, pp. 32-33; Pease, 1965, pp. 445-452; Rodriguez, 2007, pp. 51, 298; Appletons’ Cyclopaedia of American Biography, 1888, Vol. I, pp. 12-13. Dictionary of American Biography, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1936, Vol. 1, Pt. 1, pp. 40-48)

ADAMS, Charles Francis, diplomatist, son of John Quincy Adams, b. in Boston, 18 Aug., 1807; d. there, 21 Nov., 1886. When two years old he was taken by his father to St. Petersburg, where he learned German, French, and Russian. Early in 1815 he travelled all the way from St. Petersburg to Paris with his mother in a private carriage, a difficult journey at that time, and not unattended with danger. His father was soon afterward appointed minister to England, and the little boy was placed at an English boarding-school. The feelings between British and Americans was then more hostile than ever before or since, and young Adams was frequently called upon to defend with his fists the good name of his country. When he returned after two years to America, his father placed him in the Boston Latin school, and he was graduated at Harvard college in 1825, shortly after his father's inauguration as president of the United States. He spent two years in Washington, and then returned to Boston, where he studied law in the office of Daniel Webster, and was admitted to the Suffolk bar in 1828. The next year he married the youngest daughter of Peter Chardon Brooks, whose elder daughters were married to Edward Everett and Rev. Nathaniel Frothingham. From 1831 to 1836 Mr. Adams served in the Massachusetts legislature. He was a member of the whig party, but, like all the rest of his vigorous and free-thinking family, he was extremely independent in politics and inclined to strike out into new paths in advance of the public sentiment. After 1836 he came to differ more and more widely with the leaders of the whig party with whom he had hitherto acted. In 1848 the newly organized free-soil party, consisting largely of democrats, held its convention at Buffalo and nominated Martin Van Buren for president and Charles Francis Adams for vice-president. There was no hope of electing these candidates, but this little party grew, six years later, into the great republican party. In 1858 he was elected to congress by the republicans of the 3d district of Massachusetts, and in 1860 he was reelected. In the spring of 1861 President Lincoln appointed him minister to England, a place which both his father and his grandfather had filled before him. Mr. Adams had now to fight with tongue and pen for his country as in school-boy days he had fought with fists. It was an exceedingly difficult time for an American minister in England. Though there was much sympathy for the U. S. government on the part of the workmen in the manufacturing districts and of many of the liberal constituencies, especially in Scotland, on the other hand the feeling of the governing classes and of polite society in London was either actively hostile to us or coldly indifferent. Even those students of history and politics who were most friendly to us failed utterly to comprehend the true character of the sublime struggle in which we were engaged— as may be seen in reading the introduction to Mr. E. A. Freeman's elaborate "History of Federal Government, from the Formation of the Achaean League to the Disruption of the United States" (London, 1862). Difficult and embarrassing questions arose in connection with the capture of the confederate commissioners Mason and Slidell, the negligence of Lord Palmerston's government in allowing the "Alabama" and other confederate cruisers to sail from British ports to prey upon American commerce, and the ever manifest desire of Napoleon III. to persuade Great Britain to join him in an acknowledgment of the independence of the confederacy. The duties of this difficult diplomatic mission were discharged by Mr. Adams with such consummate ability as to win universal admiration. No more than his father or grandfather did he belong to the school of suave and crafty, intriguing diplomats. He pursued his ends with dogged determination and little or no attempt at concealment, while his demeanor was haughty and often defiant. His unflinching firmness bore clown all opposition, and his perfect self-control made it difficult for an antagonist to gain any advantage over him. His career in England from 1861 to 1868 must be cited among the foremost triumphs of American diplomacy. In 1872 it was attempted to nominate him for the presidency of the United States, as the candidate of the liberal republicans, but Horace Greeley secured the nomination. He was elected in 1869 a member of the board of overseers of Harvard college, and was for several years president of the board. He has edited the works and memoirs of his father and grandfather, in 22 octavo volumes, and published many of his own addresses and orations. Appleton’s Cyclopaedia of American Biography, 1888, Vol. I. pp. 12-13.

|

|

ADAMS, E. M., New York, abolitionist, American Anti-Slavery Society, Manager, 1836-37

|

|

ADAMS, George, Boston, Massachusetts, abolitionist, Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, Counsellor, 1841-42

|

|

ADAMS, John, 1735-1826, statesman, founding father, second President of the United States, opponent of slavery, father of John Quincy Adams. (Appletons’ Cyclopaedia of American Biography, 1888, Vol. I, pp. 17-23; Encyclopaedia Americana, 1829, Vol. I, pp. 44-52; Dictionary of American Biography, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1936, Vol. 1, Pt. 1, pp. 72-82)

Biography from Appletons' Cyclopaedia of American Biography:

ADAMS, John, second-president of the United States, b. in that part of the town of Braintree, Mass., which has since been set off as the town of Quincy, 31 Oct., 1785; d. there, 4 July, 1826. His great-grandfather, Henry Adams, received a grant of about 40 acres of land in Braintree in 1636, and soon afterward emigrated from Devonshire, England, with his eight sons. John Adams, the subject of this sketch, was the eldest son of John Adams and Susanna Boylston, daughter of Peter Boylston, of Brookline. His father, one of the selectmen of Braintree and a deacon of the church, was a thrifty farmer, and at his death in 1760 his estate was appraised at £1,330 9s. 6d., which in those days might have been regarded as a moderate competence. It was the custom of the family to send the eldest son to college, and accordingly John was graduated at Harvard in 1755. Previous to 1773 the graduates of Harvard were arranged in lists, not alphabetically or in order of merit, but according to the social standing of their parents. In a class of twenty-four members John thus stood fourteenth. One of his classmates was John Wentworth, afterward royal governor of New Hampshire, and then of Nova Scotia. After taking his degree and while waiting to make his choice of a profession, Adams took charge of the grammar school at Worcester. It was the year of Braddock's defeat, when the smouldering fires of a century of rivalry between France and England broke out in a blaze of war which was forever to settle the question of the primacy of the English race in the modern world. Adams took an intense interest in the struggle, and predicted that if we could only drive out “these turbulent Gallics,” our numbers would in another century exceed those of the British, and all Europe would be unable to subdue us. In sending him to college his family seem to have hoped that he would become a clergyman; but he soon found himself too much of a free thinker to feel at home in the pulpit of that day. When accused of Arminianism, he cheerfully admitted the charge. Later in life he was sometimes called a Unitarian, but of dogmatic Christianity he seems to have had as little as Franklin or Jefferson. “Where do we find,” he asks, “a precept in the gospel requiring ecclesiastical synods, convocations, councils, decrees, creeds, confessions, oaths, subscriptions, and whole cart-loads of other trumpery that we find religion encumbered with in these days?” In this mood he turned from the ministry and began the study of law at Worcester. There was then a strong prejudice against lawyers in New England, but the profession throve lustily nevertheless, so litigious were the people. In 1758 Adams began the practice of his profession in Suffolk co., having his residence in Braintree. In 1764 he was married to Abigail Smith, of Weymouth, a lady of social position higher than his own and endowed with most rare and admirable qualities of head and heart. In this same year the agitation over the proposed stamp act was begun, and on the burning questions raised by this ill-considered measure Adams had already taken sides. When James Otis in 1761 delivered his memorable argument against writs of assistance, John Adams was present in the court-room, and the fiery eloquence of Otis wrought a wonderful effect upon him. As his son afterward said, “it was like the oath of Hamilcar administered to Hannibal.” In his old age John Adams wrote, with reference to this scene, “Every man of an immense crowded audience appeared to me to go away, as I did, ready to take arms against writs of assistance. Then and there was the first scene of the first act of opposition to the arbitrary claims of Great Britain. Then and there the child Independence was born.” When the stamp act was passed, in 1765, Adams took a prominent part in a town-meeting at Braintree where he presented resolutions which were adopted word for word by more than forty towns in Massachusetts. The people refused to make use of stamps, and the business of the inferior courts was carried on without them, judges and lawyers agreeing to connive at the absence of the stamps. In the supreme court, however, where Thomas Hutchinson was chief justice, the judges refused to transact any business without stamps. This threatened serious interruption to business, and the town of Boston addressed a memorial to the governor and council, praying that the supreme court might overlook the absence of stamps. John Adams was unexpectedly chosen, along with Jeremiah Gridley and James Otis, as counsel for the town, to argue the case in favor of the memorial. Adams delivered the opening argument, and took the decisive ground that the stamp act was ipso facto null and void, since it was a measure of taxation which the people of the colony had taken no share in passing. No such measure, he declared, could be held as binding in America, and parliament had no right to tax the colonies. The governor and council refused to act in the matter, put presently the repeal of the stamp act put an end to the disturbance for a while. About this time Mr. Adams began writing articles for the Boston “Gazette.” Four of these articles, dealing with the constitutional rights of the people of New England, were afterward republished under the somewhat curious title of “An Essay on the Canon and Feudal Law.” After ten years of practice, Mr. Adams's business had become quite extensive, and in 1768 he moved into Boston. The attorney-general of Massachusetts, Jonathan Sewall, now offered him the lucrative office of advocate-general in the court of admiralty. This was intended to operate as an indirect bribe by putting Mr. Adams into a position in which he could not feel free to oppose the policy of the crown; such insidious methods were systematically pursued by Gov. Bernard, and after him by Hutchinson. But Mr. Adams was too wary to swallow the bait, and he stubbornly refused the pressing offer. In 1770 came the first in the series of great acts that made Mr. Adams's career illustrious. In the midst of the terrible excitement aroused by the “Boston Massacre” he served as counsel for Capt. Preston and his seven soldiers when they were tried for murder. His friend and kinsman, Josiah Quincy, assisted him in this invidious task. The trial was judiciously postponed for seven months until the popular fury had abated. Preston and five soldiers were acquitted; the other two soldiers were found guilty of manslaughter, and were barbarously branded on the hand with a hot iron. The verdict seems to have been strictly just according to the evidence presented. For his services to his eight clients Mr. Adams received a fee of nineteen guineas, but never got so much as a word of thanks from the churlish Preston. An ordinary American politician would have shrunk from the task of defending these men, for fear of losing favor with the people. The course pursued by Mr. Adams showed great moral courage; and the people of Boston proved themselves able to appreciate true manliness by electing him as representative to the legislature. This was in June, 1770, after he had undertaken the case of the soldiers, but before the trial. Mr. Adams now speedily became the principal legal adviser of the patriot party, and among its foremost leaders was only less conspicuous than Samuel Adams, Hancock, and Warren. In all matters of legal controversy between these leaders and Gov. Hutchinson his advice proved invaluable. During the next two years there was something of a lull in the political excitement; Mr. Adams resigned his place in the legislature and moved his residence to Braintree, still keeping his office in Boston. In the summer of 1772 the British government ventured upon an act that went further than anything which had yet occurred toward driving the colonies into rebellion. It was ordered that all the Massachusetts judges holding their places during the king's pleasure should henceforth have their salaries paid by the crown and not by the colony. This act, which aimed directly at the independence of the judiciary, aroused intense indignation, not only in Massachusetts, but in the other colonies, which felt their liberties threatened by such a measure. It called forth from Mr. Adams a series of powerful articles, which have been republished in the 3d volume of his collected works. About this time he was chosen a member of the council, but the choice was negatived by Gov. Hutchinson. The five acts of parliament in April, 1774, including the regulating act and the Boston port bill, led to the calling of the first continental congress, to which Mr. Adams was chosen as one of the five delegates from Massachusetts. The resolutions passed by this congress on the subject of colonial rights were drafted by him, and his diary and letters contain a vivid account of some of the proceedings. On his return to Braintree he was chosen a member of the revolutionary provincial congress of Massachusetts, then assembled at Concord. This revolutionary body had already seized the revenues of the colony, appointed a committee of safety, and begun to organize an army and collect arms and ammunition. During the following winter the views of the loyalist party were set forth with great ability and eloquence in a series of newspaper articles by Daniel Leonard, under the signature of “Massachusettensis.” He was answered most effectively by Mr. Adams, whose articles, signed “Novanglus,” appeared weekly in the Boston “Gazette” until the battle of Lexington. The last of these articles, which was actually in type in that wild week, was not published. The series, which has been reprinted in the 4th volume of Mr. Adams's works, contains a valuable review of the policy of Bernard and Hutchinson, and a powerful statement of the rights of the colonies. In the second continental congress, which assembled on May 10, Mr. Adams played a very important part. Of all the delegates present he was probably the only one, except his cousin, Samuel Adams, who was convinced that matters had gone too far for any reconciliation with the mother country, and that there was no use in sending any more petitions to the king. As there was a strong prejudice against Massachusetts on the part of the middle and southern colonies, it was desirable that her delegates should avoid all appearance of undue haste in precipitating an armed conflict. Nevertheless, the circumstances under which an army of 16,000 New England men had been gathered to besiege the British in Boston were such as to make it seem advisable for the congress to adopt it as a continental army; and here John Adams did the second notable deed of his career. He proposed Washington for the chief command of this army, and thus, by putting Virginia in the foreground, succeeded in committing that great colony to a course of action calculated to end in independence. This move not only put the army in charge of the only commander capable of winning independence for the American people in the field, but its political importance was great and obvious. Afterward in some dark moments of the revolutionary war, Mr. Adams seems almost to have regretted his part in this selection of a commander. He understood little or nothing of military affairs, and was incapable of appreciating Washington's transcendent ability. The results of the war, however, justified in every respect his action in the second continental congress. During the summer recess taken by congress Mr. Adams sat as a member of the Massachusetts council, which declared the office of governor vacant and assumed executive authority. Under the new provisional government of Massachusetts, Mr. Adams was made chief justice, but never took his seat, as continental affairs more pressingly demanded his attention. He was always loquacious, often too ready to express his opinions, whether with tongue or pen, and this trait got him more than once into trouble, especially as he was inclined to be sharp and censorious. For John Dickinson, the leader of the moderate and temporizing party in congress, who had just prevailed upon that body to send another petition to the king, he seems to have entertained at this time no very high regard, and he gave vent to some contemptuous expressions in a confidential letter, which was captured by the British and published. This led to a quarrel with Dickinson, and made Mr. Adams very unpopular in Philadelphia. When congress reassembled in the autumn, Mr. Adams, as member of a committee for fitting out cruisers, drew up a body of regulations, which came to form the basis of the American naval code. The royal governor, Sir John Wentworth, fled from New Hampshire about this time, and the people sought the advice of congress as to the form of government which it should seem most advisable to adopt. Similar applications presently came from South Carolina and Virginia. Mr. Adams prevailed upon congress to recommend to these colonies to form for themselves new governments based entirely upon popular suffrage; and about the same time he published a pamphlet entitled “Thoughts on Government, Applicable to the Present State of the American Colonies.” By the spring of 1776 the popular feeling had become so strongly inclined toward independence that, on the 15th of May, Mr. Adams was able to carry through congress a resolution that all the colonies should be invited to form independent governments. In the preamble to this resolution it was declared that the American people could no longer conscientiously take oath to support any government deriving its authority from the crown; all such governments must now be suppressed, since the king had withdrawn his protection from the inhabitants of the united colonies. Like the famous preamble to Townshend's act of 1767, this Adams preamble contained within itself the gist of the whole matter. To adopt it was to cross the Rubicon, and it gave rise to a hot debate in congress. Against the opposition of most of the delegates from the middle states the resolution was finally carried; “and now,” exclaimed Mr. Adams, “the Gordian knot is cut.” Events came quickly to maturity. On the 7th of June the declaration of independence was moved by Richard Henry Lee, of Virginia, and seconded by John Adams. The motion was allowed to lie on the table for three weeks, in order to hear from the colonies of Connecticut, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and New York, which had not yet declared their position with regard to independence. Meanwhile three committees were appointed, one on a declaration of independence, a second on confederation, and a third on foreign relations; and Mr. Adams was a member of the first and third of these committees. On the 1st of July Mr. Lee's motion was taken up by congress sitting as a committee of the whole; and as Mr. Lee was absent, the task of defending it devolved upon Mr. Adams, who, as usual, was opposed by Dickinson. Adams's speech on that occasion was probably the finest he ever delivered. Jefferson called him “the colossus of that debate”; and indeed his labors in bringing about the declaration of independence must be considered as the third signal event of his career. On the 12th of June congress established a board of war and ordnance, with Mr. Adams for its chairman, and he discharged the arduous duties of this office until after the surrender of Burgoyne. After the battle of Long Island, Lord Howe sent the captured Gen. Sullivan to Philadelphia, soliciting a conference with some of the members of the congress. Adams opposed the conference, and with characteristic petulance alluded to the unfortunate Sullivan as a decoy duck who had much better have been shot in the battle than sent on such a business. Congress, however, consented to the conference, and Adams was chosen as a commissioner, along with Franklin and Rutledge. Toward the end of the year 1777 Mr. Adams was appointed to supersede Silas Deane as commissioner to France. He sailed 12 Feb., 1778, in the frigate “Boston,” and after a stormy passage, in which he ran no little risk of capture by British cruisers, he landed at Bordeaux, and reached Paris on the 8th of April. Long before his arrival the alliance with France had been consummated. He found a wretched state of things in Paris, our three commissioners there at loggerheads, one of them dabbling in the British funds and making a fortune by privateering, while the public accounts were kept in the laxest manner. All sorts of agents were drawing bills upon the United States, and commanders of war vessels were setting up their claims for expenses and supplies that had never been ordered. Mr. Adams, whose habits of business were extremely strict and methodical, was shocked at this confusion, and he took hold of the matter with such vigor as to put an end to it. He also recommended that the representation of the United States at the French court should be intrusted to a single minister instead of three commissioners. As a result of this advice, Franklin was retained at Paris, Arthur Lee was sent to Madrid, and Adams, being left without any instructions, returned to America, reaching Boston 2 Aug., 1779. He came home with a curious theory of the decadence of Great Britain, which he had learned in France, and which serves well to illustrate the mood in which France had undertaken to assist the United States. England, he said, “loses every day her consideration, and runs toward her ruin. Her riches, in which her power consisted, she has lost with us and never can regain. She resembles the melancholy spectacle of a great, wide-spreading tree that has been girdled at the root.” Such absurd notions were quite commonly entertained at that time on the continent of Europe, and such calamities were seriously dreaded by many Englishman in the event of the success of the Americans. Immediately on reaching home Mr. Adams chosen delegate from Braintree to the convention for framing a new constitution for Massachusetts; but before the work of the convention was finished he was appointed commissioner to treat for peace with Great Britain, and sailed for France in the same French frigate in which he had come home. But Lord North's government was not ready to make peace, and, moreover, Count Vergennes contrived to prevent Adams from making any official communication to Great Britain of the extent of his powers. During Adams's stay in Paris a mutual dislike and distrust grew up between himself and Vergennes. The latter feared that if negotiations were to begin between the British government and the United States, they might lead to a reconciliation and reunion of the two branches of the English race, and thus ward off that decadence of England for which France was so eagerly hoping. On the other hand, Adams quite correctly believed that it was the intention of Vergennes to sacrifice the interests of the Americans, especially as concerned with the Newfoundland fisheries and the territory between the Alleghanies and the Mississippi, in favor of Spain, with which country France was then in close alliance. Americans must always owe a debt of gratitude to Mr. Adams for the clear-sightedness with which he thus read the designs of Vergennes and estimated at its true value the purely selfish intervention of France in behalf of the United States. This clearness of insight was soon to bear good fruit in the management of the treaty of 1783. For the present, Adams found himself uncomfortable in Paris, as his too ready tongue wrought unpleasantness both with Vergennes and with Franklin, who was too much under the French minister's influence. On his first arrival in Paris, society there had been greatly excited about him, as it was supposed that he was “the famous Mr. Adams” who had ordered the British troops out of Boston in March, 1770, and had thrown down the glove of defiance to George III. on the great day of the Boston tea-party. When he explained that he was only a cousin of that grand and picturesque personage he found that fashionable society thenceforth took less interest in him. In the summer of 1780 Mr. Adams was charge by congress with the business of negotiating Dutch loan. In order to give the good people of Holland some correct ideas as to American affairs he published a number of articles in the Leyden “Gazette” and in a magazine entitled “La politique hollandaise”; also “Twenty-six Letters upon Interesting Subjects respecting the Revolution in America,” now reprinted in the 7th volume of his works. Soon after Adams's arrival in Holland, England declared war against the Dutch, ostensibly because of a proposed treaty of commerce with the United States in which the burgomaster of Amsterdam was implicated with Henry Laurens, but really because Holland had joined the league headed by the empress Catharine of Russia, designed to protect the commerce of neutral nations and known as the armed neutrality. Laurens had been sent out by congress as minister to Holland but, as he had been captured by a British cruise and taken to the tower of London, Mr. Adams was appointed minister in his place. His first duty was to sign, as representing the United States, the articles of the armed neutrality. Before he had got any further, indeed before he had been recognized as minister by the Dutch government, he was called back to Paris, in July, 1781, in order to be ready to enter upon negotiations for peace with the British government. Russia and Austria had volunteered their services as mediators between George III. and the Americans; but Lord North's government rejected the offer, so that Mr. Adams had his journey for nothing, and presently went back to Holland. His first and most arduous task was to persuade the Dutch government to recognize him as minister from the independent United States. In this he was covertly opposed by Vergennes, who wished the Americans to feel exclusively dependent upon France, and to have no other friendships or alliances. From first to last the aid extended by France to the Americans in the revolutionary war was purely selfish. That despotic government wished no good to a people struggling to preserve the immemorial principles of English liberty, and the policy of Vergennes was to extend just enough aid to us to enable us to prolong the war, so that colonies and mother country might alike be weakened. When he pretended to be the disinterested friend of the Americans, he professed to be under the influence of sentiments that he did not really feel; and he thus succeeded in winning from congress a confidence to which he was in no wise entitled. But he could not hood-wink John Adams, who wrote home that the duke de la Vauguyon, the French ambassador at the Hague, was doing everything in his power to obstruct the progress of the negotiations; and in this, Adams correctly inferred, he was acting under secret instructions from Vergennes. As a diplomatist Adams was in a certain sense Napoleonic; he introduced new and strange methods of warfare, which disconcerted the perfidious intriguers of the old school, of which Vergennes and Talleyrand were typical examples. Instead of beating about the bush and seeking to foil trickery by trickery (a business in which the wily Frenchman would doubtless have proved more than his match), he went straight to the duke de la Vauguyon and bluntly told him that he saw plainly what he was up to, and that it was of no use, since “no advice of his or of the count de Vergennes, nor even a requisition from the king, should restrain me.” The duke saw that Adams meant exactly what he said, and, finding that it was useless to oppose the negotiations, “fell in with me, in order to give the air of French influence” to them. Events worked steadily and rapidly in Adams's favor. The plunder of St. Eustatius early in 1781 bad raised the wrath of the Dutch against Great Britain to fever heat. In November came tidings of the surrender of Lord Cornwallis. By this time Adams had published so many articles as to have given the Dutch some idea as to what sort of people the Americans were. He had some months before presented a petition to the states general, asking them to recognize him as minister from independent nation. With his wonted boldness he now demanded a plain and unambiguous answer to this petition, and followed up the demand by visiting the representatives of the several cities in person and arguing his case. As the reward of this persistent energy, Mr. Adams had the pleasure of seeing the independence of the United States formally recognized by Holland on the 19th of April, 1782. This success was vigorously followed up. A Dutch loan of $2,000,000 was soon negotiated, and on the 7th of October a treaty of amity and commerce, the second which was ratified with the United States as an independent nation, was signed at the Hague. This work in Holland was the fourth signal event in John Adams's career, and, in view of the many obstacles overcome, he was himself in the habit of referring to it as the greatest triumph of his life. “One thing, thank God! is certain,” he wrote; “I have planted the American standard at the Hague. There let it wave and fly in triumph over Sir Joseph Yorke and British pride. I shall look down upon the flag-staff with pleasure from the other world.” Mr. Adams had hardly time to finish this work when his presence was required in Paris. Negotiations for peace with Great Britain had begun some time before in conversations between Franklin and Richard Oswald, a gentleman whom Lord Shelburne had sent to Paris for the purpose. One British ministry had already been wrecked through these negotiations, and affairs had dragged along slowly amid endless difficulties. The situation was one of the most complicated in the history of diplomacy. France was in alliance at once with Spain and with the United States, and her treaty obligations to the one were in some respects inconsistent with her treaty obligations to the other. The feeling of Spain toward the United States was intensely hostile, and the French government was much more in sympathy with the former than with the latter. On the other hand, the new British government was not ill-disposed toward the Americans, and was extremely ready to make liberal concessions to them for the sake of thwarting the schemes of France. In the background stood George III., surly and irreconcilable, hoping that the negotiations would fail; and amid these difficulties they doubtless would have failed had not all the parties by this time had a surfeit of bloodshed. The designs of the French government were first suspected by John Jay, soon after his arrival in Paris. He found that Vergennes was sending a secret emissary to Lord Shelburne under an assumed name; he ascertained that the right of the United States to the Mississippi valley was to be denied; and he got hold of a despatch from Marbois, the French secretary of legation at Philadelphia, to Vergennes, opposing the American claim to the Newfoundland fisheries. As soon as Jay learned these facts he proceeded, without the knowledge of Franklin, to take steps toward a separate negotiation between Great Britain and the United States. When Adams arrived in Paris, Oct. 26, he coincided with Jay's views, and the two together overruled Franklin. Mr. Adams's behavior at this time was quite characteristic. It is said that he left Vergennes to learn of his arrival through the newspapers. It was certainly some time before he called upon him, and he took occasion, besides, to express his opinions about republics and monarchies in terms that courtly Frenchman thought very rude. Adams agreed with Jay that Vergennes should be kept as far as possible in the dark until everything was completed, and so the negotiation with Great Britain went on separately. The annals of modern diplomacy have afforded few stranger spectacles. With the indispensable aid of France we had just got the better of England in fight, and now we proceeded amicably to divide territory and commercial privileges with the enemy, and to make arrangements in which our not too friendly ally was virtually ignored. In this way the United States secured the Mississippi valley, and a share in the Newfoundland fisheries, not as a privilege but as a right, the latter result being mainly due to the persistence of Mr. Adams. The point upon which the British commissioners most strongly insisted was the compensation of the American loyalists for the hardships they had suffered during the war; but this the American commissioners resolutely refused. The most they could be prevailed upon to allow was the insertion in the treaty of a clause to the effect that congress should recommend to the several state governments to reconsider their laws against the tories and to give these unfortunate persons a chance to recover their property. In the treaty, as finally arranged, all the disputed points were settled in favor of the Americans; and, the United States being thus virtually detached from the alliance, the British government was enabled to turn a deaf ear to the demands of France and Spain for the surrender of Gibraltar. Vergennes was outgeneralled at every turn. On the part of the Americans the treaty of 1783 deserves to be ranked as one of the most brilliant triumphs of modern diplomacy. Its success was about equally due to Adams and to Jay, whose courage in the affair was equal to their skill, for they took it upon themselves to disregard the explicit instructions of congress. Ever since March, 1781, Vergennes had been intriguing with congress through his minister at Philadelphia, the chevalier de la Luzerne. First he had tried to get Mr. Adams recalled to America. Failing in this, he had played his part with such dexterous persistence as to prevail upon congress to send most pusillanimous instructions to its peace commissioners. They were instructed to undertake nothing whatever in the negotiations without the knowledge and concurrence of “the ministers of our generous ally, the king of France,” that is to say, of the count de Vergennes; and they were to govern themselves entirely by his advice and opinion. Franklin would have followed these instructions; Adams and Jay deliberately disobeyed them, and earned the gratitude of their countrymen for all coming time. For Adams's share in this grand achievement it must certainly be cited as the fifth signal event in his career. By this time he had become excessively home sick, and as soon as the treaty was arranged he asked leave to resign his commissions and return to America. He declared he would rather be “carting street-dust and marsh-mud” than waiting where he was. But business would not let him go. In September, 1783, he was commissioned, along with Franklin and Jay, to negotiate a commercial treaty with Great Britain. A sudden and violent fever prostrated him for several weeks, after which he visited London and Bath. Before he had fully recovered his health he learned that his presence was required in Holland. In those days, when we lived under the articles of confederation, and congress found it impossible to raise money enough to meet its current expenses, it was by no means unusual for the superintendent of finance to draw upon our foreign ministers and then sell the drafts for cash. This was done again and again, when there was not the smallest ground for supposing that the minister upon whom the draft was made would have any funds wherewith to meet it. It was part of his duty as envoy to go and beg the money. Early in the winter Mr. Adams learned that drafts upon him had been presented to his bankers in Amsterdam to the amount of more than a million florins. Less than half a million florins were on hand to meet these demands, and, unless something were done at once, the greater part of this paper would go back to America protested. Mr. Adams lost not a moment in starting for Holland, but he was delayed by a succession of terrible storms on the German ocean, and it was only after fifty-four days of difficulty and danger that he reached Amsterdam. The bankers had contrived to keep the drafts from going to protest, but news of the bickerings between the thirteen states had reached Holland. It was believed that the new nation was going to pieces, and the regency of Amsterdam had no money to lend it. The promise of the American government was not regarded as valid security for a sum equivalent to about $300,000. Adams was obliged to apply to professional usurers, from whom, after more humiliating perplexity, he succeeded in obtaining a loan at exorbitant interest. In the meantime he had been appointed commissioner, along with Franklin and Jefferson, for the general purpose of negotiating commercial treaties with foreign powers. As his return to America was thus indefinitely postponed, he sent for his wife, with their only daughter and youngest son, to come and join him in France, where the two elder sons were already with him. In the summer of 1784 the family was thus re-united, and began house-keeping at Auteuil, near Paris. A treaty was successfully negotiated with Prussia, but, before it was ready to be signed, Mr. Adams was appointed minister to the court of St. James, and arrived in London in May, 1785. He was at first politely received by George III., upon whom his bluff and fearless dignity of manner made a considerable impression. His stay in England was, however, far from pleasant. The king came to treat him with coldness, sometimes with rudeness, and the royal example was followed by fashionable society. The American government was losing credit at home and abroad. It was unable to fulfil its treaty engagements as to the payment of private debts due to British creditors, and as to the protection of the loyalists. The British government, in retaliation, refused to surrender the western posts of Ogdensburg, Oswego, Niagara, Erie, Sandusky, Detroit, and Mackinaw, which by the treaty were to be promptly given up to the United States. Still more, it refused to make any treaty of commerce with the United States, and neglected to send any minister to represent Great Britain in this country. It was generally supposed in Europe that the American government would presently come to an end in general anarchy and bloodshed; and it was believed by George III. and the narrow-minded politicians, such as Lord Sheffield, upon whose cooperation he relied, that, if sufficient obstacles could be thrown in the way of American commerce to cause serious distress in this country, the United States would repent of their independence and come straggling back, one after another, to their old allegiance. Under such circumstances it was impossible for Mr. Adams to accomplish much as minister in England. During his stay there he wrote his “Defence of the American Constitutions,” a work which afterward subjected him at home to ridiculous charges of monarchical and anti-republican sympathies. The object of the book was to set forth the advantages of a division of the powers of government, and especially of the legislative body, as opposed to the scheme of a single legislative chamber, which was advocated by many writers on the continent of Europe. The argument is encumbered by needlessly long and sometimes hardly relevant discussions on the history of the Italian republics. Finding the British government utterly stubborn and impracticable, Mr. Adams asked to be recalled, and his request was granted in February, 1788. For the “patriotism, perseverance, integrity, and diligence” displayed in his ten years of service abroad he received the public thanks of congress. He had no sooner reached home than he was elected a delegate from Massachusetts to the moribund continental congress, but that body expired before he had taken his seat in it. During the summer the ratification of the new constitution was so far completed that it could be put into operation, and public attention was absorbed in the work of organizing the new government. As Washington was unanimously selected for the office of president, it was natural that the vice-president should be taken from Massachusetts. The candidates for the presidency and vice-presidency were voted for without any separate specification, the second office falling to the candidate who obtained the second highest number of votes in the electoral college. Of the 69 electoral votes, all were registered for Washington, 34 for John Adams, who stood second on the list; the other 35 votes were scattered among a number of candidates. Adams was somewhat chagrined at this marked preference shown for Washington. His chief foible was enormous personal vanity, besides which he was much better fitted by temperament and training to appreciate the kind of work that he had himself done than the military work by which Washington had won independence for the United States. He never could quite understand how or why the services rendered by Washington were so much more important than his own. The office of vice-president was then more highly esteemed than it afterward came to be, but it was hardly suited to a man of Mr. Adams's vigorous and aggressive temper. In one respect, however, he performed a more important part while holding that office than any of his successors. In the earlier sessions of the senate there was hot debate over the vigorous measures by which Washington's administration was seeking to reëtablish American credit and enlist the conservative interests of the wealthier citizens in behalf of the stability of the government. These measures were for the most part opposed by the persons who were rapidly becoming organized under Jefferson's leadership into the republican party, the opposition being mainly due to dread of the possible evil consequences that might flow from too great an increase of power in the federal government. In these debates the senate was very evenly divided, and Mr. Adams, as presiding officer of that body, was often enabled to decide the question by his casting vote. In the first congress he gave as many as twenty casting votes upon questions of most vital importance to the whole subsequent history of the American people, and on all these occasions he supported Washington's policy. During Washington's administration grew up the division into the two great parties which have remained to this day in American politics—the one known as federalist, afterward as whig, then as republican; the other known at first as republican and afterward as democratic. John Adams was by his mental and moral constitution a federalist. He believed in strong government. To the opposite party he seemed much less a democrat than an aristocrat. In one of his essays he provoked great popular wrath by using the phrase “the well-born.” He knew very well that in point of hereditary capacity and advantages men are not equal and never will be. His notion of democratic equality meant that all men should have equal rights in the eye of the law. There was nothing of the communist or leveller about him. He believed in the rightful existence of a governing class, which ought to be kept at the head of affairs; and he was supposed, probably with some truth, to have a predilection for etiquette, titles, gentlemen-in- waiting, and such things. Such views did not make him an aristocrat in the true sense of the word, for in nowise did he believe that the right to a place in the governing class should be heritable; it was something to be won by personal merit, and should not be withheld by any artificial enactments from the lowliest of men, to whom the chance of an illustrious career ought to be just as much open as to “the well-born.” At the same time John Adams differed from Jefferson and from his cousin, Samuel Adams, in distrusting the masses. All the federalist leaders shared this feeling more or less, and it presently became the chief source of weakness to the party. The disagreement between John Adams and Jefferson was first brought into prominence by the breaking out of the French revolution. Mr. Adams expected little or no good from this movement, which was like the American movement in no respect whatever except in being called a revolution. He set forth his views on this subject in his “Discourses on Davila,” which were published in a Philadelphia newspaper. Taking as his text Davila's history of the civil wars in France in the 16th century, he argued powerfully that a pure democracy was not the best form of government, but that a certain mixture of the aristocratic and monarchical elements was necessary to the permanent maintenance of free government. Such a mixture really exists in the constitution of the United States, and, in the opinion of many able thinkers, constitutes its peculiar excellence and the best guarantee of its stability. These views gave great umbrage to the extreme democrats, and in the election of 1792 they set up George Clinton, of New York, as a rival candidate for the vice-presidency; but when the votes were counted Adams had 77, Clinton 50, Jefferson 4, and Aaron Burr 1. During this administration Adams, by his casting vote, defeated the attempt of the republicans to balk Jay's mission to England in advance by a resolution entirely prohibiting trade with that country. For a time Adams quite forgot his jealousy of Washington in admiration for the heroic strength of purpose with which he pursued his policy of neutrality amid the furious efforts of political partisans to drag the United States into a rash and desperate armed struggle in support either of France or of England. In 1796, as Washington refused to serve for a third term, John Adams seemed clearly marked out as federalist candidate for the succession. Hamilton and Jay were in a certain sense his rivals; but Jay was for the moment unpopular because of the famous treaty that he had lately negotiated with England, and Hamilton, although the ablest man in the federalist party, was still not so conspicuous in the eyes of the masses of voters as Adams, who besides was surer than any one else of the indispensable New England vote. Having decided upon Adams as first candidate, it seemed desirable to take the other from a southern state, and the choice fell upon Thomas Pinckney, of South Carolina, a younger brother of Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. Hamilton now began to scheme against Mr. Adams in a manner not at all to his credit. He had always been jealous of Adams because of his stubborn and independent character, which made it impossible for him to be subservient to a leader. There was not room enough in one political party for two such positive and aggressive characters. Already in the election of 1788 Hamilton had contrived to diminish Adams's vote by persuading some electors of the possible danger of a unanimous and therefore equal vote for him and Washington. Such advice could not have been candid, for there was never the smallest possibility of a unanimous vote for Mr. Adams. Now in 1796 he resorted to a similar stratagem. The federalists were likely to win the election, but had not many votes to spare; the contest was evidently going to be close. Hamilton accordingly urged the federalist electors, especially in New England, to cast all their votes alike for Adams and Pinckney, lest the loss of a single vote by either one should give the victory to Jefferson, upon whom the opposite party was clearly united. Should Adams and Pinckney receive an exactly equal number of votes, it would remain for a federalist congress to decide which should be president. The result of the election showed 71 votes for John Adams, 68 for Jefferson, 59 for Pinckney, 30 for Burr, 15 for Samuel Adams, and the rest scattering. Two electors obstinately persisted in voting for Washington. When it appeared that Adams had only three more votes than Jefferson, who secured the second place instead of Pinckney, it seemed on the surface as if Hamilton's advice had been sound. But from the outset it had been clear (and no one knew it better than Hamilton) that several southern federalists would withhold their votes from Adams in order to give the presidency to Pinckney, always supposing that the New England electors could be depended upon to vote equally for both. The purpose of Hamilton's advice was to make Pinckney president and Adams vice-president, in opposition to the wishes of their party. This purpose was suspected in New England, and while some of the southern federalists voted for Pinckney and Jefferson, eighteen New Englanders, in voting for Adams, withheld their votes from Pinckney. The result was the election of a federalist president with a republican vice-president. In case of the death, disability, or removal of the president, the administration would fall into the hands of the opposite party. Clearly a mode of election that presented such temptations to intrigue, and left so much to accident, was vicious and could not last long. These proceedings gave rise to a violent feud between John Adams and Alexander Hamilton, which ended in breaking up the federalist party, and has left a legacy of bitter feelings to the descendants of those illustrious men. The presidency of John Adams was stormy. We were entering upon that period when our party strife was determined rather by foreign than by American political issues, when England and France, engaged in a warfare of Titans, took every occasion to browbeat and insult us because we were supposed to be too feeble to resent such treatment. The revolutionary government of France had claimed that, in accordance with our treaty with that country, we were bound to support her against Great Britain, at least so far as concerned the defence of the French West Indies. The republican party went almost far enough in their sympathy with the French to concede these claims, which, if admitted by our government, would immediately have got us into war with England. On the other hand, the hatred felt toward France by the extreme federalists was so bitter that any insult from that power was enough to incline them to advocate war against her and in behalf of England. Washington, in defiance of all popular clamor, adhered to a policy of strict neutrality, and in this he was resolutely followed by Adams. The American government was thus obliged carefully and with infinite difficulty to steer between Scylla and Charybdis until the overthrow of Napoleon and our naval victories over England in 1812-'14 put an end to this humiliating state of things. Under Washington's administration Gouverneur Morris had been for some time minister to France, but he was greatly disliked by the anarchical group that then misruled that country. To avoid giving offence to the French republic, Washington had recalled Morris and sent James Monroe in his place, with instructions to try to reconcile the French to Jay's mission to England. Instead of doing this, Monroe encouraged the French to hope that Jay's treaty would not be ratified, and Washington accordingly recalled him and sent Cotesworth Pinckney in his place. Enraged at the ratification of Jay's treaty, the French government not only gave a brilliant ovation to Monroe, but refused to receive Pinckney, and would not even allow him to stay in Paris. At the same time, decrees were passed discriminating against American commerce. Mr. Adams was no sooner inaugurated as president than he called an extra session of congress, to consider how war with France should be avoided. It was decided to send a special commission to France, consisting of Cotesworth Pinckney, John Marshall, and Elbridge Gerry. The directory would not acknowledge these commissioners and treat with them openly; but Talleyrand, who was then secretary for foreign affairs, sent some of his creatures to intrigue with them behind the scenes. It was proposed that the envoys should pay large sums of money to Talleyrand and two or three of the directors, as bribes, for dealing politely with the United States and refraining from locking up American ships and stealing American goods. When the envoys scornfully rejected this proposal, a new decree was forthwith issued against American commerce. The envoys drew up an indignant remonstrance, which Gerry hesitated to sign. Wearied with their fruitless efforts, Marshall and Pinckney left Paris. But, as Gerry was a republican, Talleyrand thought it worth while to persuade him to stay, hoping that he might prove more compliant than his colleagues. In March, 1798, Mr. Adams announced to congress the failure of the mission, and advised that the preparations already begun should be kept up in view of the war that now seemed almost inevitable. A furious debate ensued, which was interrupted by a motion from the federalist side, calling on the president for full copies of the despatches. Nothing could have suited Mr. Adams better. He immediately sent in copies complete in everything except that the letters X., Y., and Z. were substituted for the names of Talleyrand's emissaries. Hence these papers have ever since been known as the “X. Y. Z. despatches.” On the 8th of April the senate voted to publish these despatches, and they aroused great excitement both in Europe and in America. The British government scattered them broadcast over Europe, to stir up indignation against France. In America a great storm of wrath seemed for the moment to have wrecked the republican party. Those who were not converted to federalism were for the moment silenced. From all quarters came up the war-cry, “Millions for defence; not one cent for tribute.” A few excellent frigates were built, the nucleus of the gallant little navy that was by and by to win such triumphs over England. An army was raised, and Washington was placed in command, with the rank of lieutenant-general. Gerry was recalled from France, and the press roundly berated him for showing less firmness than his colleagues, though indeed he had not done anything dishonorable. During this excitement the song of “Hail, Columbia” was published and became popular. On the 4th of July the effigy of Talleyrand, who had once been bishop of Autun, was arrayed in a surplice and burned at the stake. The president was authorized to issue letters of marque and reprisal, and for a time war with France actually existed, though it was never declared. In February, 1799, Capt. Truxtun, in the frigate “Constellation,” defeated and captured the French frigate “L’Insurgente” near the island of St. Christopher. In February, 1800, the same gallant officer in a desperate battle destroyed the frigate “La Vengeance,” which was much his superior in strength of armament. When the directory found that their silly and infamous policy was likely to drive the United States into alliance with Great Britain, they began to change their tactics. Talleyrand tried to crawl out by disavowing his emissaries X. Y. Z., and pretending that the American envoys had been imposed upon by irresponsible adventurers. He made overtures to Vans Murray, the American minister at the Hague, tending toward reconciliation. Mr. Adams, while sharing the federalist indignation at the behavior of France, was too clear-headed not to see that the only safe policy for the United States was one of strict neutrality. He was resolutely determined to avoid war if possible, and to meet France half-way the moment she should show symptoms of a return to reason. His cabinet were so far under Hamilton's influence that he could not rely upon them; indeed, he had good reason to suspect them of working against him. Accordingly, without consulting his cabinet, on 18 Feb., 1799, he sent to the senate the nomination of Vans Murray as minister to France. This bold step precipitated the quarrel between Mr. Adams and his party, and during the year it grew fiercer and fiercer. He joined Ellsworth, of Connecticut, and Davie, of North Carolina, to Vans Murray as commissioners, and awaited the assurance of Talleyrand that they would be properly received at Paris. On receiving this assurance, though it was couched in rather insolent language by the baffled Frenchman, the commissioners sailed Nov. 5. On reaching Paris, they found the directory overturned by Napoleon, with whom as first consul they succeeded in adjusting the difficulties. This French mission completed the split in the federalist party, and made Mr. Adams's reëlection impossible. The quarrel with the Hamiltonians had been further embittered by Adams's foolish attempt to prevent Hamilton's obtaining the rank of senior major-general, for which Washington had designated him, and it rose to fever-heat in the spring of 1800, when Mr. Adams dismissed his cabinet and selected a new one. Another affair contributed largely to the downfall of the federalist party. In 1798, during the height of the popular fury against France, the federalists in congress presumed too much upon their strength, and passed the famous alien and sedition acts. By the first of these acts, aliens were rendered foible to summary banishment from the United States at the sole discretion of the president; and any alien who should venture to return from such banishment was liable to imprisonment at hard labor for life. By the sedition act any scandalous or malicious writing against the president or either house of congress was liable to be dealt with in the United States courts and punished by fine and imprisonment. This act contravened the constitutional amendment that forbids all infringement of freedom of speech and of the press, and both acts aroused more widespread indignation than any others that have ever passed in congress. They called forth from the southern republicans the famous Kentucky and Virginia resolutions of 1798-'99, which assert, though in language open to some latitude of interpretation, the right of a state to “nullify” or impede the execution of a law deemed unconstitutional.

In the election of 1800 the federalist votes were given to John Adams and Cotesworth Pinckney, and the republican votes to Jefferson and Burr. The count showed 65 votes for Adams, 64 for Pinckney, and 1 for Jay, while Jefferson and Burr had each 73, and the election was thus thrown into the house of representatives. Mr. Adams took np part in the intrigues that followed. His last considerable public act, in appointing John Marshall to the chief justiceship of the United States, turned out to be of inestimable value to the country, and was a worthy end to a great public career. Very different, and quite unworthy of such a man as John Adams, was the silly and puerile fit of rage in which he got up before daybreak of the 4th of March and started in his coach for Massachusetts, instead of waiting to see the inauguration of his successful rival. On several occasions John Adams's career shows us striking examples of the demoralizing effects of stupendous personal vanity, but on no occasion more strikingly than this. He went home with a feeling that he had been disgraced by his failure to secure a reëlection. Yet in estimating his character we must not forget that in his resolute insistence upon the French mission of 1799 he did not stop for a moment to weigh the probable effect of his action upon his chances for reelection. He acted as a true patriot, ready to sacrifice himself for the welfare of his country, never regretted the act, and always maintained that it was the most meritorious of his life. “I desire,” he said, “no other inscription over my grave-stone than this: Here lies John Adams, who took upon himself the responsibility of the peace with France in the year 1800.” He was entirely right, as all disinterested writers now agree.

After so long and brilliant a career, he now passed a quarter of a century in his home at Quincy (as that part of Braintree was now called) in peaceful and happy seclusion, devoting himself to literary work relating to the history of his times. In 1820 the aged statesman was chosen delegate to the convention for revising the constitution of Massachusetts, and labored unsuccessfully to obtain an acknowledgment of the equal rights, political and religious, of others than so-called Christians. His friendship with Jefferson, which had been broken off by their political differences, was resumed in his old age, and an interesting correspondence was kept up between the two. As a writer of English, John Adams in many respects surpassed all his American contemporaries; his style was crisp, pungent, and vivacious. In person he was of middle height, vigorous, florid, and somewhat corpulent, quite like the typical John Bull. He was always truthful and outspoken, often vehement and brusque. Vanity and loquacity, as he freely admitted, were his chief foibles. Without being quarrelsome, he had little or none of the tact that avoids quarrels; but he harbored no malice, and his anger, though violent, was short-lived. Among American public men there has been none more upright and honorable. He lived to see his son president of the United States, and died on the fiftieth anniversary of the declaration of independence and in the ninety-first year of his age. His last words were, “Thomas Jefferson still survives.” But by a remarkable coincidence, Jefferson had died a few hours earlier the same day. See “Life and Works of John Adams,” by C. F. Adams (10 vols., Boston, 1850-'56); “Life of John Adams,” by J. Q. and C. F. A dams (2 vols., Philadelphia, 1871); and “John Adams,” by J. T. Morse, Jr. (Boston, 1885).

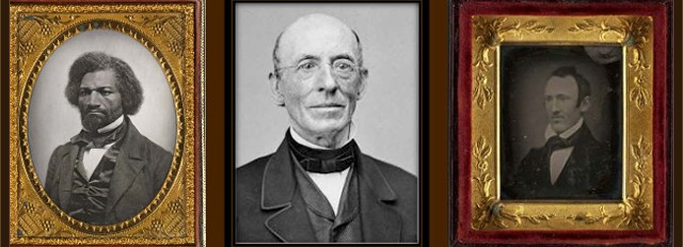

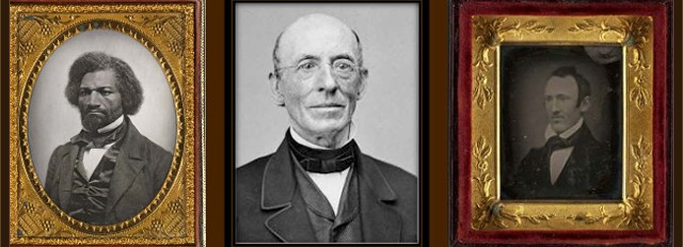

The portrait that forms the frontispiece of this volume is from a painting by Gilbert Stuart, which was executed while Mr. Adams was president and is now in the possession of his grandson. The one on page 16 was taken when he was a youth. The houses represented on page 15 are those in which President John Adams and his son John Quincy Adams were born. Appletons’ Cyclopædia of American Biography, 1888.

Biography from National Portrait Gallery of Distinguished Americans:

AMONG the earliest settlers of the English colonies in New England was a family by the name of Adams. One of the grantees of the charter of Charles the First to the London Company was named Thomas Adams, though it does not appear that he was of those who emigrated with Governor Winthrop, in 1630.

It appears by the Governor’s journal, that in 1634 there came a considerable number of colonists, under the pastoral superintendence of the Rev. Thomas Parker, in a vessel from Ipswich, in the county of Essex, in the neighborhood of which is the small town of Braintree.

There was, it seems, after their arrival, some difficulty in deciding where they should be located. It was finally determined that Mount Wollaston, situated within the harbor, and distant about nine miles from the three mountains, and whence the intrusive merry mountaineer Morton had been expelled, should, with an enlarged boundary, be annexed to Boston; and the lands within that boundary were granted in various proportions to individuals, chiefly, if not entirely, of the new company from Ipswich.

The settlement soon increased; and feeling, like all the original settlements in New England, the want of religious instruction and social worship, found it a great inconvenience to travel nine or ten miles every Sunday to reach the place of their devotions. In 1636 they began to hold meetings, and to hear occasional preachers, at Mount Wollaston itself. Three years afterwards they associated themselves under a covenant as a Christian Church; and in 1640 were incorporated as a separate town, by the name of Braintree.

Of this town Henry Adams, junior, was the first town-clerk; and the first pages of the original town records, still extant, are in his handwriting. He was the oldest of eight sons, with whom his father, Henry Adams, had emigrated, probably from Braintree in England, and who had arrived in the vessel from Ipswich 1634. Henry Adams the elder, died in 1646, leaving a widow, and a daughter named Ursula, besides the eight sons above-mentioned. He had been a brewer in England, and had set up a brewery in his new habitation. This establishment was continued by the youngest but one of his sons, named Joseph. The other sons sought their fortunes in other towns, and chiefly among their first settlers. Henry, who had been the first town clerk of Braintree; removed, at the time of the incorporation of Medfield in 1652, to that place, and was again the first town-clerk there.

Joseph, the son who remained at Braintree, was born in 1626; was at the time of the emigration of the family from England, a boy of eight years old, and died at the age of sixty-eight in 1694, leaving ten children,—five sons and five daughters.

One of these sons, named John, settled in Boston, and was father of Samuel Adams, and grandfather of the revolutionary patriot of that name.

Another son, named also Joseph, was born in 1654; married Hannah Bass, a daughter of Ruth Alden, and grand-daughter of John Alden of the May Flower, and died in 1736 at the age of eighty-two.

His second son named John, born in 1689, was the father of JOHN ADAMS, the subject of the present memoir. His mother was Susanna, daughter of Peter Boylston, and niece of Dr. Zabdiel Boylston, renowned as the first introducer of inoculation for the small-pox in the British dominions.

This JOHN ADAMS was born on the 30th October, 1735, at Braintree. His father’s elder brother, Joseph, had been educated at Harvard College; and was for upwards of sixty years minister of a Congregational church at Newington, New Hampshire.

John Adams, the father, was a farmer of small estate and a common school education. He lived and died, as his father and grandfather had done before him, in that mediocrity of condition between affluence, and poverty, most propitious to the exercise of the ordinary duties of life, and to the enjoyment of individual happiness. He was for many years a deacon of the church, and a select man of the town, without enjoying or aspiring to any higher dignity. He was in his religious opinions, like most of the inhabitants of New England at that time, a rigid Calvinist, and was desirous of bestowing upon his eldest son the benefit of a classical education, to prepare him for the same profession with that of his elder brother, the minister of the gospel at Newington.

JOHN ADAMS, the son, had at that early age no vocation for the Church, nor even for a college education. Upon his father’s asking him to what occupation in life he would prefer to be raised, he answered that he wished to be a farmer. His father, without attempting directly to control his inclination, replied that it should be as he desired. He accordingly took him out with himself the next day upon the farm, and gave him practical experience of the labors of the plough, the spade, and the scythe. At the close of the day the young farmer told his father that he would go to school. He retained, however, his fondness for farming to the last years of his life.

He was accordingly placed under the tuition of Mr. Marsh, the keeper of a school then residing at Braintree, and who, ten years afterwards, was also the instructor of Josiah Quincy, the celebrated patriot, who lived but to share the first trials and to face the impending terrors of the revolution.

In 1751, at the age of sixteen, JOHN ADAMS was admitted as a student at Harvard College, and in 1755 was graduated as Bachelor of Arts. The class to which he belonged stands eminent on the College catalogue, for the unusual number of men distinguished in after-life. Among them were Samuel Locke, some time President of the College; Moses Hemmenway, subsequently a divine of high reputation; Sir John Wentworth, Governor of the province of New Hampshire; William Browne, a judge of the Superior Court of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, and afterwards Governor of the island of Bermuda; David Sewall, many years judge of the District Court of the United States in the district, and afterwards State of Maine; and Tristram Dalton, a Senator of the United States. Three of these had so far distinguished themselves while under-graduates, that, in the traditions of the College, it was for many years afterwards known by the sons of Harvard as the class of Adams, Hemmenway, and Locke.

John Adams, the father, had thus given to his eldest son a liberal education to fit him for the gospel ministry. He had two other sons, Peter Boylston and Elihu, whom he was educating to the profession which JOHN had at first preferred, of farmers. In this profession Peter Boylston continued to the end of a long life, holding for many years a commission as a justice of the peace, and serving for some time the town of Quincy as their representative in the legislature of the Commonwealth. He died in 1822 at the age of eighty-four leaving numerous descendants among the respectable inhabitants of Quincy and of Boston. Elihu, at the commencement of the Revolution entered the army as a captain, and with multitudes of others fell a victim to the epidemic dysentery of 1775. He left two sons and one daughter, whose posterity reside in the towns of Randolph, (originally a part of Braintree,) Abington, and Bridgewater. The daughter was the mother of Aaron Hobart, several years a member of the House of Representatives of the United States, and afterwards of the Council of the Commonwealth.

Among the usages of the primitive inhabitants of the villages of New England, a liberal, that is, a college education, was considered as an outfit for life, and equivalent to the double portion of an eldest son. Upon being graduated at the College in 1755, JOHN ADAM’S, at the age of twenty, had received this double portion, and was thenceforth to provide for himself.

“The world was all before him, and Providence his guide.”

At the commencement, when he was graduated, there were present one or more of the select-men of the town of Worcester, which was then in want of a teacher for the town school. They proposed to Mr. Adams to undertake this service, and he accepted the invitation. He repaired immediately to Worcester, and took upon him the arduous duties of his office; pursuing at the same time the studies which were to prepare him for the ministry.

His entrance thus upon the theatre of active life was at a period of great political excitement. Precisely at the time when he went to reside at Worcester, occurred the first incidents of the seven years’ war, waged between France and Britain for the mastery of the North American continent. The disaster of Braddock’s defeat and death happened precisely at that time, like the shock of an earthquake throughout the British colonies. Politics were the speculation of every mind—the prevailing topic of every conversation. It was then that he wrote to his kinsman, Nathaniel Webb, that prophetic letter which has been justly called a literary phenomenon, and which shadowed forth the future revolution of Independence, and the naval glories of this Union.

His father had fondly cherished the hope that he was raising, by the education of his son, a monumental pillar of the Calvinistic church; and he himself, reluctant at the thought of disappointing the hopes of his father, and unwilling to embrace a profession laboring then under strong prejudices unfavorable to it among the people of New England, had acquiesced in the purpose which had devoted him to the gospel ministry. But the progress of his theological studies soon gave him an irresistible distaste for the Calvinistic doctrines. The writings of Archbishop Tillotson, then at the summit of their reputation; the profound analysis of Bishop Butler, with his sermons upon human nature and upon the character of Balaam, took such hold upon his memory, his imagination, and his judgment, that they extirpated from his mind every root of Calvinism that had been implanted in it; and the philosophical works of Bolingbroke, then a dazzling novelty in the literary world, although wholly successless in their tendency to shake his faith in the sublime and eternal truths of the gospel, contributed effectively to wean him from the creed of the Genevan Reformer.